Audio CDs (3) of the Real Estate Principles Textbook - $29.95 may be purchased through the American Schools ONLINE Catalog at: http://americanschoolsonline.com Listen to sample audios at: http://americanschoolsonline.com/audio

SHORT

INTRODUCTION TO CALIFORNIA REAL ESTATE PRINCIPLES,

© 1994 by Home Study, Inc. dba American Schools

Click on link to go to:

Table of Contents; Chapter I: Real Property; Chapter II: Legal Ownership; Chapter III: Agency & Ethics; Chapter IV: Contracts; Chapter V: Real Estate Mathematics; Chapter VI: Financing; Chapter VII: Mortgage Insurance; Chapter VIII: Appraisal; Chapter IX: Transfers of Real Estate; Chapter X: Property Management; Chapter XI: Land Control; Chapter XII: Taxation; Chapter XIII: Fair Housing Laws; Chapter XIV: Macroeconomics; Chapter XV: Legal Professional Requirements; Chapter XVI: Notarial Law; Chapter XVII: Selling Real Estate; Chapter XVIII: Trust Funds Handling; Glossary; Index.

Chapter II: Legal Ownership

Educational Objectives: Learn about Description by Metes

& Bounds, Description by Section and Township, Assessor's Maps, Titles and Estates,

Priorities in Recording, Assuring Marketability of

Title (Abstract of Title, Title Insurance), Mechanic's Lien, Attachments and Judgments, Easements,

Restrictions, Encroachments,

Homestead, R. E. TERMS

GLOSSARY, INDEX.

Legal

Descriptions of Property

When buying and selling real estate, parties

must know exactly what constitutes the physical boundaries of a parcel of real

estate. Thus, a legal description of a property is a necessary element of the

real estate sales transaction.

A proper description of real property is one that

will hold up in a court of law, and is therefore legal, and that will allow a

reasonably knowledgeable person to locate and determine the physical boundaries

of a parcel of real estate. The three accepted methods for legally describing

property are:

- metes and bounds;

- government rectangular survey system, and;

- subdivision lot and block of a recorded plat

map.

Note that a street address is usually not

sufficient as a proper and legal description because it does not adequately

define the physical boundaries of the property.

The system of metes and bounds is the oldest

method for describing property. Metes are measures of distance such as inches,

rods, feet or yards; bounds are natural or man-made landmarks or monuments used

to locate the property. Used most often in rural areas, this method describes

property by defining its boundaries and the distances and directions between

them. A metes and bounds description starts at a point of beginning and then

indicates the direction of the boundary line and the distance to each monument

around the perimeter of the property back to the point of beginning.

A tract of land beginning in X County would be

described as follows: Beginning at the intersection of the east line of Dobbs

Road and the south line of McClennan Drive; then east along the south line of

McClennan Drive 1200 feet; then South 15 degrees East 220 feet to the center

line of Hogtown Creek; then northwest along the center line of Hogtown Creek to

its intersection with the East line of Dobbs Road, then north 110 feet, along

the East line of Dobbs Road to the point of beginning.

The description must always close by returning

to the point of beginning so that the parcel of property will be fully

enclosed. When used in urban areas, the metes and bounds method makes reference

to streets and other man-made improvements instead of naturally occurring

landmarks.

If there is a discrepancy between the actual

distance to a stated monument and the linear distance, the actual distance to

the monument will prevail. A parcel can be described accurately regardless of

what happens to monuments provided there is a fixed, permanently identifiable

point of beginning (POB), such as a reference to sections, townships, or ranges

from the Governmental Survey System.

Permanent reference marks (PRM) or bench marks

are located throughout the country to aid surveyors in work involving elevation

and altitude. A bench mark is a reference point of known elevation and location

established by the U. S. Geodetic Survey, and usually identified by a marker of

stone or other durable material permanently fixed in the ground. Where there is

no datum (assumed point) in an area, surveyors may begin at an established

bench mark for location and elevation.

Government Rectangular Survey System

Created

in 1785, the government rectangular survey system (GRSS) uses a grid system

imposed on a map of land to locate and describe a parcel of property. This

method begins by dividing land with north-south lines called principal

meridians and east-west lines called base lines. These lines are located by

reference to longitude and latitude. The intersection of a principal meridian

and a base line is known as an initial point. All land descriptions are

referenced to this point.

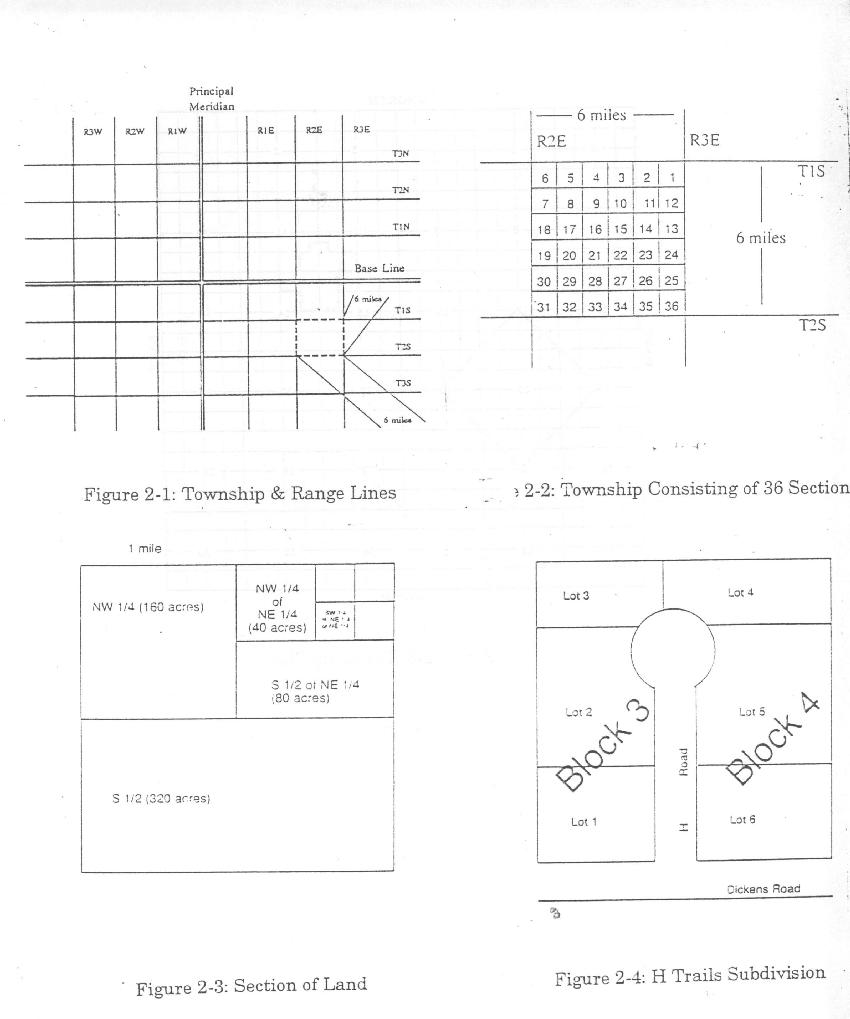

Running

parallel to a principal meridian are range lines, spaced at six-mile intervals

to the east and west of the principal meridian. Township lines run parallel to

a base line and are spaced at six-mile intervals to the north and south. These

township and range lines compose a grid consisting of six-mile squares, known

as townships, on a map. The second township south and the third township east

of the initial point would be referenced as T2S, R3Eas seen in Figure 2-1 at

the end of this chapter.

Once a township has been defined, it is further

divided into 36 parcels, each one-mile square. These one-mile square parcels

are known as sections. Each section is composed of 640 acres. Note that the

numbering of the sections begins from right to left from the upper right hand

corner and continues right to left, then down and left to right, until all 36

sections are identified.

The GRSS would identify the section highlighted

in Figure 2-2 at the end of this chapter as Section 10, T2S, R3E of the

principal meridian and base line.

From here it is relatively easy to subdivide a

section using a system of directions and fractions. In the Figure 2-3 at the

end of this chapter section 10 has been divided into four quarters and further

divided to illustrate the ease with which this system can be used.

Subdivision Lot and Block of a Recorded Plat Map

An alternate way to describe real estate, used

primarily in urban areas, is by reference to a recorded survey, called a plat

map. Plat maps are prepared by developers seeking to subdivide land. The map

includes a detailed description of the subdivision showing the arrangement of

the lots and blocks, streets, sewers, water mains, easements, green space,

parks, and other physical features. Each lot and block is assigned a number or

letter and the exact dimensions of each lot are noted on the plat. If the

proposed subdivision is approved by the appropriate local agency, such as the

planning board, then the plat map is entered into the Official Records of the

county where the land is located.

In describing real estate with this method, the

lot and block number, name of the subdivision plat are used, as shown in Figure

2-4 at the end of this chapter.

Lot 5, Block 4 of H Trails Subdivision, as shown

in plat thereof recorded in Plat Book 2, page 10 of maps, City Y, in County X,

California.

A lot and block description that is not part of

an approved and recorded plat map is not an accepted legal description. An

owner of a lot in an unrecorded subdivision, therefore, has no verifiable way

of identifying or locating the property.

The plat will reveal the shape of each lot in

relation to other lots, and all lots and blocks will be numbered. The main

essentials are

1. A definite starting point, clearly set

out, with the corners marked accurately with permanent monuments set out on the

plat. The plat corners must accurately fit the tract of land.

2. A careful and accurate survey of

the tract into streets, parks (if any), lots, alleys and the placing of

permanent stones or iron stakes at the corner of all blocks and similar stakes

at the corners of lots.

3. Platting of the subdivision on

paper showing all blocks, lots, streets, alleys, etc. The exact size or dimension

of each lot, block, alley, or street, and any other information which in after

years may be of assistance in definitely locating any property in the

subdivision.

The plat must be executed and

acknowledged by the owner with streets, parks, etc., dedicated to the public.

After the plat has been filed, it can not be rescinded or vacated without all

of the property owners in the addition joining in the vacation, or unless a

successful suit filed in the District Court asking for a cancellation or vacation

of the plat. Original additions or parts thereof are sometimes later

resubdivided or amended. For instance, the size of the lots are changed or made

to face a different direction. An amended plat or resubdivision of less than

the entire original addition, however, will not have the effect of waiving or

changing the restrictions in the original plat. The legality of such replats,

amended plats, or re-subdivision is often questioned by attorneys, and

frequently a lot will be described in more than one way or by metes and bounds

description to cure such objections.

OFFICIAL RECORDS

Public records are maintained in every

city, town, and county in the United States. They are generally maintained in

each county seat. These records serve to establish legal ownership of real

property, give notice of encumbrances, and establish the priority of liens.

Placing a document in the Official

Records is known as recording. Note that any instrument affecting title to real

estate, such as a deed or mortgage, should be recorded as soon as possible to

give constructive notice to all persons of the grantee's or mortgagee's

interest in property. Constructive knowledge is presumed of all persons, by

law, as a result of recording documents, such as deed and mortgages, in the

Official Records. This differs from actual notice which is given by legal

possession of real property or by handing the person a copy of the document. As

a general rule, priority of interests is established according to the sequence,

or time, of entry into the Official Records.

Both the obligation and benefit of

recording a new deed go to the grantee, or new owner. The grantee must record

the deed as soon as possible to avoid a situation where the grantor sells the

property a second time to another buyer. If Buyer Two, without knowing of the

sale to Buyer One, were to record his/her deed before Buyer One, Buyer Two

would have a superior claim of ownership. Buyer One's only recourse in this

event would be to sue the seller in court for fraud. The time, expense, and

aggravation can easily be avoided by prompt recording of a new deed.

Types of Official Records

Licensees must be familiar with several

types of public records to provide clients with the best possible service.

The alphabetical index lists all recorded

documents according to the last name of the parties. Typically included is an

abbreviation of the type of document, the date it was recorded, the book number

and page number in which it is recorded, and a very brief description of the

property, such as in what range, section and township it is located, or the

subdivision lot number. Such overall indices have generally replaced the

grantor-grantee and mortgagor-mortgagee indices. Knowing the name of either

party, a broker can find all records in that person's name. For instance, John

Black sold his home to Sally Green. Knowing the last name of either the grantor

or grantee will enable the broker to initiate a title search. Upon finding the

grantee, the broker searching the records can find the grantor, the date of the

transaction, and type of transfer. A look at the recorded document will provide

further information such as complete legal description, amount of taxes paid,

and restrictions. Plat books allow the broker to locate a particular lot in a

subdivision, its size, the features of the other lots, most easements, roads,

the name of the original developer, and surveyor.

A tract index, sometimes referred to as a

lot and block index, lists deeds and other documents affecting title to

property according to legal description rather than by the names of the grantor

and grantee. In urban areas, knowing the name of the subdivision in which a

property is located starts a search using this index. On the other hand, plat

maps of a subdivision include a unique number for each block with the lots on

that block assigned their own numbers. From there one can readily look up the

lot description in the index. In rural areas the legal descriptions contained

in the tract index are most frequently classified according to the Government

Rectangular Survey System by township and section.

A search of the chain of title using the

tract index is easier than using the alphabetical or grantor-grantee index

because all transactions related to a specific parcel are recorded on the same

page. The disadvantage of the tract index is the difficulty and expense in

maintaining it. Note: Local governments seldom maintain a tract index due to

its expense; such indices are commonly found in private title and abstract

companies.

(The following reprinted by permission

from the CalBRE Reference Book, p. 74-80, 83-85.)

California's Principal Base Lines and

Meridians

California has three base lines and

meridians. They are the Humboldt Base Line and Meridian, located in the

northwestern part of the State; the Mt. Diablo Base Line and Meridian, located

in the central part of the State, and the San Bernardino Base Line and Meridian

located in the southern part of the State. Townships are further divided into

sections. Each township contains 36 sections, each section theoretically, is

one mile square and therefore contains one square mile of land. The township is

six sections long and six sections wide and therefore contains 36 square miles.

A section may then be divided for the purpose of having a more particular and

specific description, into quarter-sections and fractions of quarter-sections.

Correction Lines

Due to the spherical shape of the earth,

the sections along the north and west boundaries of each township are

approximately fifty feet shorter than the south side. Because of this

irregularity additional lines called guide meridians are run every 24 miles

east and west of the meridian. Other lines called standard parallels, are run every

24 miles north and south of the base line. These guide meridians and standard

parallels also are known as correction lines.

In the original government survey system,

lakes, streams and other features were sometimes encountered which created

fractional pieces of land less than a quarter section in size. These fractional

segments were identified by number. The specific lot number then became the

legal description for that land parcel and these parcels were called government

lots.

Today, the loss of acreage due to

township correction lines and unascertainable errors are placed in the quarter

sections bordering the western and northern boundaries of the township. These

geographical divisions which would otherwise qualify as quarter-quarter

sections are also referred to as "government lots." A government lot

necessarily does not contain a standard number of acres.

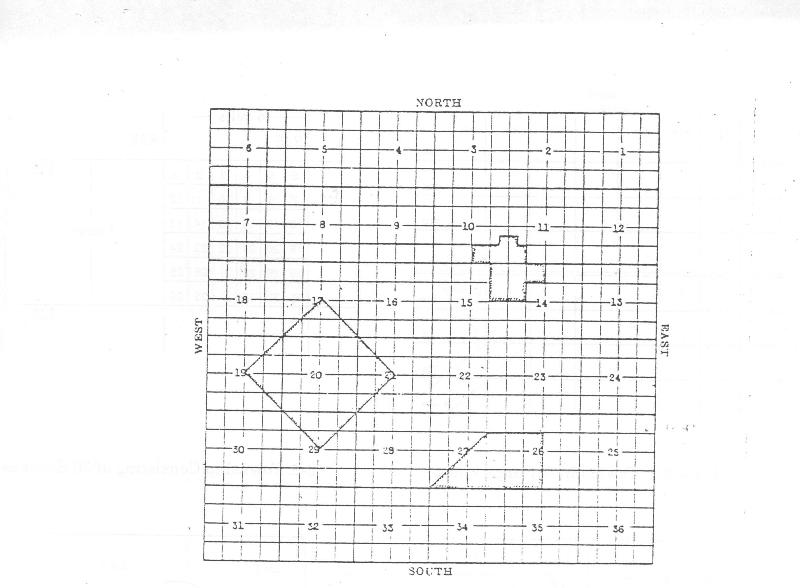

Township Plat

1.

Beginning at the NE. corner of SW.1/4 of Sec. 17, thence southeasterly to the

NW. corner of the SE. 1/4 of Section 21, thence southwesterly to the SE. corner

of the NW. 1/4 of Sec. 29, thence northwesterly to the SW. corner of the NE.

1/4 of Sec.19, thence northeasterly back to the point of beginning.

2. The

SE. 1/4 of the NE. 1/4 of the SE. 1/47 and the S. 1/2 of the SE.1/4 of Sec. 10;

the SW. 1/4 of the NW. 1/4 of the SW. 1/4 and the SW. 1/4 of the SW.1/4 of

Sec.11, the E. 1/2 of the NE.1/4 of Sec. 15; and the NW. 1/4 of Sec.14,

excepting the SE. 1/4 thereof.

3. Beginning

at the NW. corner of the SE. 1/4 of the NE.1/4 of Sec. 27, thence due east

3,960 ft., thence due south 3,960 ft., then due west 7,920 ft., thence

northeasterly in a straight line to the point of beginning.

Method

of Locating Tracts on Township Plat

Some

examinations given by the California Bureau of Real Estate for real estate broker and

salesperson licenses contain problems based on descriptions similar to the

foregoing examples.

Note:

In working out Example No. 2 above shown in Figure 2-5 at the end of this

chapter, the result is depicted in the irregularly shaped figure outlined in

the upper right area of the plat. The shaded figure includes parts of Sections

10, 11, 14 and 15. In working out this problem, the following procedure may be

used:

Read

along to the first break in the description, which in this case is a comma,

"The SE. 1/4 of the NE. 1/4 of the SE.1/4", This phrase describes one

portion of the area, and reading further you see that it is a part of Section

10.Now go back to the break, the comma, and start back from there. The SE.1/4

(of Sec. 10) locate that. Proceeding back, the NE 1/4 (of the SE. 1/4/ of

Sec.10) locate that. Then back the SE.1/4 (of the NE. 1/4 of the SE. 1/4/ of

Sec.10) locate that area and outline it as you have now completed the first

segment of the entire description. Since this segment is 1/4 of a quarter of a

quarter-section (1/4 of 1/4 of 160 acres), you have outlined a 10-acre parcel.

Now

following the portion of the description that you have just completed appears

the complete phrase "and the S.1/2 of the SE.1/4 of Section

10,".Locate the SE.1/4 (of Sec. 10).Then take the S.1/2 (of the SE.1/4 of

Sec.10) and, since this completes the segment, outline that portion which is

two complete squares of 40 acres each.

Now

you have completed the description up to the first semicolon. Proceeding read

along to the new break, again a comma. "The SW.1/4 of the NW.1/4 of the

SW.1/4,".Here again you have a complete phrase, and reading on you

discover that it refers to a portion of Section 11.Now back to the end of the

phrase (the comma) and proceed back from there the SW.1/4 (of Sec. 11)?locate

that. Going back the SW.1/4 (of the NW.1/4 of the SW.1/4 of Sec.11). Since this

completes the phrase outline this additional 10-acre parcel on your plat.

Now,

go on to the next complete phrase which is "and the SW.1/4 of the SW.1/4

of Sec.11."Locate the SW.1/4 (of Sec.11) and outline the SW.1/4 of that. This

will add another 40-acre square to your pictured description.

Reading

on from the portion you have just completed (from the second semicolon in the

written description), you find the next complete phrase "The E.1/2 of the

NE.1/4 of Sec.15." Locate the NE.1/4 (of Sec.15) and outline the east 1/2

of that area. Thus, two more small squares of 40 acres each are shaded in on

your plat and you have come to the last phrase in the written description which

is "and the NW.1/4 of Sec.14 excepting the SE.1/4 thereof." You,

therefore, locate the NW.1/4 of Sec.14 and shade the whole of it, with the

exception of its SE.1/4, thus adding three more of the small squares of 40

acres each to the area covered by the written description.

The

delineation of the described area on the plat is now complete. By adding as you

went along, the acreage of the area you have shaded; or by computing the total

of complete shaded small squares with any fractional portion thereof and

multiplying by 40, you have the total number of acres in the described area. In

the problem just presented, the total acreage is 340.

Example.

Deed descriptions, in order to eliminate error, usually spell out directions

and the fractional part of the section, followed by the abbreviation in

parentheses, or vice versa. For instance: The southwest quarter (SW.1/4 ) of

the northeast quarter (NE.1/4) of Section 6 Township 7 South, (T.7 S.), Range

14 East (R.14 E.), Mt. Diablo Base and Meridian (M.D.B.& M.).

Lot

and Block Descriptions

Under

the California Subdivision Map Act all new subdivisions must be mapped or platted.

The map shows the relationship of the subdivision to other lands, and each

parcel in the new subdivision is delineated and identified. When accepted by

county or city authority the map is filed in the county recorder's office and

has official status. Afterwards, any parcel in the subdivision is simply

described in legal instruments by reference to the tract name or number and

block and lot numbers. To this is added, City of , County of

.This makes for simplicity in describing property as: "Lot

14, Block B, Parkview Addition (as recorded July 17, 1926, Book 2, Page 49 of

maps), City of Sacramento, County of Sacramento, State of California."

Within 90 days after the establishment of

points or lines, a land surveyor or civil engineer who has made a survey in

conformity with land surveying practices shall file a record of survey relating

to boundaries or property lines with the county surveyor in the county in which

the survey was made. This record of survey map shall disclose

(1) material evidence or physical change

which does not appear on any map previously recorded in the office of the

county recorder,

(2) a material

discrepancy with information of record with the county,

(3) any evidence

that might result in alternate positions of lines or points, or

(4) the

establishment of lines not shown on a recorded map which are not ascertainable

from an inspection of the map without trigonometric calculations.

The county surveyor, after examining a

record of survey map filed with the surveyor's office, shall then file it with

the county recorder.

The county assessor may prepare and file

in the assessor's office an accurate map of any land in the county and may

number or letter the parcels in a manner approved by the board of supervisors.

Section 327 of the Revenue and Taxation Code provides "that land shall not

be described in any deed or conveyance by a reference to any such map unless

such map has been filed for record in the office of the county recorder of the

county in which such land is located."

Informal

Method of Land Description

In the absence of a title report, it is

often found convenient to refer to a specific parcel of realty by street

number, name (e.g., "The Norris Ranch"), or blanket reference (e.g.,

"my lot on High Street").These methods are legal, but title companies

ordinarily will not insure title derived through such a description. Usually

the specific boundaries of the grant must be established by one of the formal

methods of description as set forth above, before title insurance can be

obtained.

If the boundary is a public road, the

owner of land abutting on it is presumed to own to the center of the road, but

the contrary may be shown.

A deed to a parcel in a subdivision

showing a dedicated street adjoining will, unless the contrary intent appears,

carry the title of the grantor to the center of the street subject to the

rights of the public to the use of the street. Owners of property abutting on a

main or public highway have a peculiar right in that highway distinct from the

public whether or not they own the fee thereof. Upon vacation, they might still

have a right to ingress and egress. Words "except" and

"reserving" as used in descriptions of property are not conclusive in

determining whether or not the fee title to the portion in question is being

conveyed. An innocent looking phrase may be omitted, or the wrong course given,

either of which may change the entire complexion of the description and thus

exclude property intended to be included, or include property which the party

executing the instrument did not own. Although descriptions may fail because of

omissions, elaboration can sometimes result in a void or uncertain conveyance.

A recording system was adopted by the

California Legislature, modeled after the system established by the original

American Colonies. It was strictly an American device for safeguarding the

ownership of land. Recording consists of copying the instrument in the Grantee-Grantor

Indices and indexing the instrument under the names of the parties.

The Recording Act of California provides

that, after being acknowledged, any instrument or judgment affecting the title

to or possession of real property may be recorded.

An order, depending upon the specific

nature of the order, may be recorded in an:

. index of deeds, grants and transfers

(grantor index);

. index of deeds labeled

"Grantees";

. index to

transcripts of judgments labeled "Transcripts of Judgments";

. index of attachments labeled

"Attachments";

. index of

notices of the pending of an action labeled "Notices of Actions"; and

. indices

labeled "General Index of Grantors" and "General Index of

Grantees".

The word "instrument" as used

in the Recording Act means "some paper signed and delivered by one person

to another, transferring the title to, or giving a lien on, property or giving

a right to a debt or duty." (Hoag v. Howard, 55 Cal.564.) Instrument does

not necessarily include every writing purporting to affect real property.

Instrument does include deeds, mortgages, leases, land contracts, deeds of

trust and agreements between or among landowners.

Purpose of Recording Statutes

The general purpose of recording statutes

is to permit, rather than to require, the recordation of any instrument which

affects the title to or possession of real property, and to penalize the person

who fails to take advantage of the privilege of recording. The recording

statutes are intended to provide that instruments affecting title or possession

to real property will be recorded in a public office so that purchasers and

others dealing with the title to property may in good faith find out about and

rely upon the ownership of the real property as shown by the record of

instruments recorded in the designated public office. The Recording Act does

not specify any particular time within which an instrument must be recorded.

Time of recording is of course very important to the bona fide purchaser and/or

lender since the purchaser or lender is protected only by properly using the

recording statutes.

As between conflicting claims to the same

parcel of land, priority of recordation will ordinarily determine the rights of

the parties. Instruments affecting real property must be recorded by the county

recorder in the county within which the property is located. If the property

lies in more than one county, the instrument, or certified copy of the record,

must be recorded in each county in which the property is located in order to

impart notice in the respective counties. If it is necessary to record a

document written in a foreign language, such as Spanish, the recorder must

permanently file the foreign language instrument with a certified translation attached.

In those counties in which a photographic method of recording is employed, the

whole instrument, including the foreign language instrument and the translation

thereof, may be recorded and the original instrument may be returned to the

party who has left it for recording.

(End of CalBRE Reference Book excerpt)

The only true "evidence of

title" is the county's records. The purpose of recording any instrument is

to give notice to the world of the transaction. Recording a deed or any

document that affects ownership in land is not compulsory, but is a right of

the holder. If such documents are recorded, the chain of title continues on

record .

The recorder will note on the instrument

the filing number and the exact time at which the document was filed, including

the year, month, day, hour, and minute that it was received. The contents of

the document are then reproduced and filed in the appropriate book of records.

The original instrument is returned to the person who left it to be recorded.

The recorded instrument is a matter of public record and anyone desiring to

examine information regarding a particular parcel of property may do so by

visiting the county courthouse where the document is recorded .

Present interests in real property are

protected if documents affecting the title are recorded. All subsequent

recordation of instruments affecting the same property will be subordinate to

the right of the present interest holder. Recordation of subsequent interest in

real property protects the interest against claimants whose interests have not

yet been recorded. This conforms to the general recording maxim, "first to

record is first in rights." Known as the race notice concept, the first to

record wins the "race to the court house."

A

properly executed deed is effectual between the parties without recording, but

in order to be effectual against all the world, it must be recorded in the

proper office. Though no more used in California, the Torrens system of

evidencing title is used in several states. The system is such that, at any

time, the original certificate of title will reveal the names of current owners

and encumbrances (such as mortgages and judgments) recorded against the real

property. Those states which have adopted the Torrens system have continued to

maintain public records so that persons wishing to continue the traditional

form of title substantiation may do so.

Title recordation acts as a means of

protecting title to real property against all persons who may later claim a

right against the property. Recording is constructive notice to the world, a

legal presumption that everyone has been informed of the existence and content

of the document.

A chain of title is a record of a

property's grantors and grantees, linking one owner to the next throughout the

legal history of the parcel of land. Whenever the link is broken or unclear, a

cloud is created and there is a flaw in the title. All recorded instruments

affecting a parcel of real property are a part of the chain of title, indexed

in the order of their actual occurrence.

As recorded documents are extremely

difficult and time-consuming to examine, the major evidence of title has become

the abstract. To the average purchaser, the abstract affords no knowledge of

the state of the title to the real estate. An attorney's opinion is needed to

inform the prospective purchaser of the nature of the seller's title and of any

defects, liens, encumbrances, or other rights which might be disclosed by the

abstract.

All counties in the state provide for the

recording, in a public office, of every document by which any estate or

interest in land is created, transferred, encumbered, or otherwise affected.

These public records furnish a reliable history of the title or ownership of

the tract of land. The abstract of title is a summary or a copy of every

recorded instrument affecting the title to the tract of real estate covered by

the abstract and is compiled by a duly licensed abstractor who conducts a title

search. If covered by the abstractor's certificate, "filed"

instruments which are not technically recorded instruments may also be

included. These are such documents as security agreements, financing

statements, chattel mortgages and certain liens.

The law provides that no document

affecting the right in real estate shall be valid against any person who does

not have actual knowledge of the rights of the parties unless that document is

recorded. Therefore, an innocent and unknowing purchaser or encumbrancer who

acts in ignorance of an unrecorded instrument is reasonably protected. However,

for an innocent buyer to become a bona fide purchaser, and prevail over a prior

purchaser of the same real property, three conditions must exist:

1. The innocent purchaser must be

without knowledge of the prior claim at the time of the purchase;

2. The purchase must be for value; and

3. The document must be the first

recorded.

In effect, the purchaser for value must

win the race to the recording office and be without notice of the prior claim

at the time value was given.

Marketable title to real property is

generally determined by an examination of an abstract of title. The examiner

will issue a title report as to the interest of grantors and their parties in a

parcel of real property.

The buyer's title report, generally

called the purchaser's title report, is the chief instrument upon which the

buyer relies. It represents an attorney's comments, opinions, and requirements

concerning the state of the title to the property, as disclosed in the abstract

delivered. It is written solely for the buyer from the buyer's point of view.

The buyer should not rely on a

mortgagee's title report since it is written with an entirely different goal in

mind. Many defects are of no interest to the mortgagee but may be of great

concern to the purchaser who may have to pay later to have them cleared.

The mortgagee will try to obtain a title

report relating to the mortgaged property making sure that there are no

outstanding liens or encumbrances which may be superior to that of the intended

mortgagee. The mortgagee is simply looking for "security" for the

investment. It will not be the mortgagee's problem or expense to render the

title marketable.

The abstractor is not a guarantor of the

title to the real estate. The law imposes upon the abstractor only the duty to

exercise due care in searching the title and in the preparation of the

abstract. The abstractor can be held liable for any loss caused the purchaser

as a result of negligence in omission of a document from the abstract or the

incorrect summarization to the content of the instrument. Likewise, an attorney

can only be held liable for damages which are caused by negligence in the

examination of the abstract. For example, the attorney is liable for any loss

caused by failure to discover an existing recorded lien contained in the

abstract.

No evidence of title can completely and

conclusively reveal the exact state of the title to real property. For

instance, an abstract may indicate that the seller has clear title, but the

chain of title may contain a forged deed. There is no way of knowing from the

abstract whether or not a deed is forged and, of course, such deed passes no

title. Also, an abstract will not reveal the rights of parties in possession.

The abstract may show title in one person but another may have a superior right

through adverse possession. With an abstract and an opinion, together with an

examination of the property itself, the buyer can be reasonably certain that a

good title can be obtained.

The usual means of curing a defect or a

cloud on the title to property are by obtaining quitclaim deeds from all other

parties who might have an interest in the property or by bringing an action to

quiet title.

Title Insurance

Title insurance is a contract which

protects the insured against loss occurring through defects in the title to real

property. The risk of loss, as in other policies of insurance, is transferred

from the property owner to a responsible insurer. A title company will not

insure a bad title any more than a life insurance company will insure a person

who is terminally ill.

Basically, a title insurance policy

provides that the company will indemnify the owner against any loss sustained

as a result of a defect in the title to the real estate, provided that the

defect is not specifically excluded in the policy. Further, the company usually

agrees to defend at its expense any lawsuit attacking the title where such

attack is based on a claimed defect covered by the insurance provisions.

Examples of typical standard exclusions which the title policy does not insure

against are:

1. Rights and claims of parties in

possession not shown of record, including unrecorded easements.

2. Any statement of facts an accurate

survey would show.

3.

Mechanic's liens, or any rights thereto, where

no notice of such liens or rights appear of record.

4.

4. Taxes and assessments not yet due

or payable and special assessments not yet certified to the treasurer's office.

For additional consideration,

all-inclusive owner's title policies may be obtained covering standard

exclusions.

The date of the policy is important. The

title insurance company guarantees against loss occurring because of defects

existing at or before the date of the policy. Defects which come into existence

subsequent to the date of insurance of the title policy are not covered.

Should the title insurance company pay a

loss within the scope of the policy, the principle of subrogation provides that

the company may attempt to collect the loss from a third party in the place of

the insured.

Title insurance companies will issue

policies to both the owner and the mortgagee. The fee or premium of the title

policy, unlike other insurance, is paid only once and the policy continues in

force without further payment. The premium, as with other insurance, is based

upon the amount of insurance purchased. The owner's title policy is not

transferable. Therefore, when the property is resold, the new purchaser should

obtain a reissue title policy. The mortgagee need not obtain a reissue policy.

The mortgagee's title policy does not

protect the owner's interest in the property. A mortgagee's policy will protect

only the mortgagee and only to the extent of the mortgagee's interest, whatever

that may be. The equity of the owner is protected only by an owner's policy. In

the case of mortgagee's policy, if the insurer pays the mortgagee, the

insurance company could enforce the mortgage against the mortgagor .

(The following reprinted by permission

from the CalBRE Reference Book, p. 118-119)

Standard Policy

The standard policy of title insurance in

addition to risks of record protects against:

Off-record hazards as forgery (e. g., a

forged deed in the chain of record title), impersonation, and lack of capacity

of a party to any transaction involving title to the land (e. g., a deed of an

incompetent or an agent whose authority has terminated, or of a corporation

whose charter has expired); the possibility that a deed of record was not in

fact delivered with intent to convey title; the loss which might arise from the

lien of federal estate taxes, which is effective without notice upon death;

and, the expense, including attorneys' fees, incurred in defending the

title-whether the plaintiff prevails or not.

The standard policy of title insurance

does not however protect the policyholder against defects in the title known to

the holder to exist at the date of the policy and not previously disclosed to

the insurance company; nor against easements and liens which are not shown by

the public records; nor against rights or claims of persons in physical

possession of the land, yet which are not shown by the public records (since

the insurer normally does not inspect the property) ; nor against rights or

claims not shown by public records, yet which could be ascertained by physical

inspection of the land, or by appropriate inquiry of persons on the land, or by

a correct survey; nor against mining claims, reservations in patents, or water

rights; nor against zoning ordinances.

These limitations are not as dangerous as

they might appear to be. To a considerable degree they can be eliminated by

careful inspection by the purchaser or his or her agent (lenders) of the land

involved, and routine inquiry as to the status of persons in possession.

However, if desired, most of these risks can be covered by special endorsement

or use of extended coverage policies at added premium cost.

A. L. T. A. Policy (for lenders)

In

California many loans secured by realty have been made by out-of-state

insurance companies which were not in a position to make personal inspection of

the properties involved except at disproportionate expense. For them and other

nonresident lenders, the special A.L. T.A. (American Land Title Association)

policy was developed. It expands the risks normally insured against under the

standard policy to include the following: Rights of parties in physical

possession, including tenants and buyers under unrecorded instruments;

reservations in patents; and most importantly unmarketability of title. The new

ALTA Loan Policy, approved for use in California on February 8, 1988, includes

added cover age; for example, recorded notices of enforcement of excluded

matters (like zoning), as well as recorded notices of defects, liens, or

encumbrances affecting title that result from a violation of matters excluded

from policy coverage, and water rights. Needless to say the insurance company

issues such a policy only after itself obtaining a competent survey and a

physical inspection of the property.

Extended Coverage

The American Land Title Association has

adopted an owner's extended coverage policy (designated as A. L.T. A. Owner’s

Policy [10-21 87]) that provides to buyers or owners the same protection that

the A. L. T. A. policy gives lenders. But note that even in these policies no

protection is afforded against defects on other matters concerning the title

which are known to the insured to exist at the date of the policy yet have not

previously been communicated in writing to the insurer, nor against

governmental regulations concerning occupancy and use. The former limitation is

self-explanatory; the latter limitation exists because zoning regulations

concern the condition of the land rather than the condition of title.

Under the provisions of the Insurance

Code of California each title insurance company organized under the laws of

this State must have at least $500,000 paid-in capital represented by shares of

stock, and must deposit with the Insurance Commissioner a "guarantee

fund" of $100,000 in cash or approved securities. The purpose of this

deposit is to secure protection for title insurer policy holders. A title

insurer must also set apart annually, as a title insurance surplus fund, a sum

equal to 10 percent of its premiums collected during the year, until this fund

equals the lesser of 25 percent of the paid-in capital of the company or

$1,000,000.Policies of title insurance are now almost universally used in

California largely in the standardized forms prepared by the California Land

Title Association, which is the trade organization of the title companies of

the state. Every title insurer must adopt and make available to the public a

schedule of fees and charges for title policies. The law prohibits a title

insurance company from paying, either directly or indirectly, any commission,

rebate or other consideration as an inducement for or as compensation on any

title insurance business, escrow or other title business in connection with

which a title policy is issued.

(End of CalBRE Reference Book excerpt)

LIMITATIONS OF TITLE

Encumbrances

An adverse interest affecting title is

known as an encumbrance. It is the right or interest in property held by others

who are not the legal owners of the property. An encumbrance is any claim,

lien, charge, or liability attached to and binding on real property which may

affect its value, or burden, obstruct, or impair the use of the property.

Although it may lessen the value of the title, it does not necessarily prevent

the transfer of ownership.

Public and private actions can have the effect

of limiting the ability of the landowner to exercise absolute control over the

condition and use of real property. Deed restrictions, easements, licenses,

water rights, and encroachments are all examples of such encumbrances or

controls.

Restrictions

are placed in the deed to control a landowner's use of real property. The

grantor may place restrictions upon the right to use the real estate conveyed.

Such restrictions must be reasonable and not contrary to public policy. The use

of restrictions, usually called deed restrictions or restrictive covenants, is

an old practice arising from the rights of property. Owners have the right of

free alienation; that is, they may dispose of their estates in any manner they

may elect. Deed restrictions, once established, normally run with the land and

are a limitation upon the use of all future grantees.

Restrictions are most frequently

encountered in the development of subdivisions wherein the limitation is for

the benefit of all the landowners. Typical restrictions deal with the minimum

size of the house, type of material that may be used, and exclusion of

commercial establishments. Well formulated restrictions have a stabilizing

effect upon property value. Home owners are protected against forbidden uses.

They can rely on the knowledge that a business will not be established next

door and that their neighbors house must conform to certain minimum standards.

Violations of restrictions can be enjoined through a court action brought by

any party for whose benefit the restrictions were imposed.

Court enforcement of just deed

restrictions is possible to the extent that it can be proved that a restriction

has been violated. Any action may be brought to require the violator to conform

to the deed restriction. Enforcement may be sought by the parties to the

original deed which contained the restriction and by those persons who are not

parties to the agreement if the restriction is imposed for their benefit (e.g.,

lot buyers within a subdivision).

Deed restrictions may be given an express

lifetime by expressing their duration in the deed. Otherwise, such restrictions

will terminate by material change in the neighborhood, by unanimous agreement

between or among affected parties, and by merger in which one landowner

acquires the interest of all persons owning subject to the restriction. Court

action will usually be required to properly effect such termination.

An easement is a right of way or right to

use another's real property or a portion thereof. An easement holder claims no

title to the real property over which the easement exists; rather, an easement

carries with it the right to enter and use the property within definable limits.

There are two general types of easements.

The easement may be either appurtenant or it may be in gross. An easement

appurtenant attaches to and runs with ownership of land. An easement in gross

belongs to its owner personally and such right does not pass with transfer of

ownership of land.

Easements may be created by a voluntary

act or by operation of law. A voluntary act would be by deed or by contract. If

an easement is created by contract, the contract must be in writing to be

enforced because easements are interests in real property covered by the statue

of frauds. An easement may be created by granting such right in a deed, or it

may arise through a specific deed reservation of an easement by the grantor of

real property.

Easements may also come into existence by

implication or by prescription. An easement by implication would be recognized

in buyers who purchase land which is totally inaccessible to a public highway

except across land retained by the seller. Since the buyers have access rights,

right to ingress and egress to and from their land, the buyers obtain an

easement by implication over the seller's land (this is also called an easement

by necessity). An easement by prescription is one obtained by continuous use of

another's property for the statutory period. If such use is open, hostile (contrary

to the rights of the landowner), continuous, and uninterrupted for the

statutory period, an easement is recognized in favor of the user.

Dominant and servient parcels are common

terms used in connection with easements. An easement appurtenant to travel

across a neighbor's property is a dominant tenement. Property over which an

easement runs in favor of another parcel of real estate is the servient

tenement.

An easement may be terminated by a

written release given by the easement owner to the affected landowner. The

writing could be by quitclaim deed which is a conveyance by the easement owner

of all right, title, and interest in the affected parcel. An easement may be

terminated by merger in which the owner of either the dominant or servient

parcel acquires ownership of the other parcel. Mutual agreement, abandonment,

end of the necessity (regarding an easement by necessity), destruction of the

servient estate, acquisition of the servient estate by a bona fide purchaser (a

person having neither actual or constructive knowledge of the easement), and

severance are other means of terminating easements.

License

A license is not a right or an estate in

land, nor is it an encumbrance against land. It is a personal privilege to make

reasonable use of the real property of the licensor. Unlike an easement, a

license is revocable by the granting party at any time. A license may be oral

or in writing, and it may or may not be based upon a contract. Death of either

party will terminate a license. Examples of a license would be the privilege to

hunt on the property of a neighbor or to park an automobile in a parking lot.

Also in this category are tickets to theaters or sporting events.

An

encroachment is the wrongful extension of a structure or improvement into the

property of another. Buildings, fences, and other structures may encroach on

adjacent land. Most encroachments are revealed by an accurate land survey. The

party encroached upon may or may not have the ability to have the encroachment

removed, depending upon the circumstances.

If an encroachment has been present for

the statutory period, the owner of the encroaching structure may assert a right

to the affected land on the basis of adverse possession (title by

prescription). If the owner of such structure cannot claim adverse possession,

the party encroached upon may bring action to have the encroachment removed on

the grounds of trespass.

Note: If the encroachment is slight

(perhaps measurable in inches), the cost of removal great, and the cause an

excusable mistake, courts will not require removal but may award dollar damages.

Other types of encumbrances are those

which have an effect on the transferability of real property. These are

generally monetary in nature.

Liens

A lien is a right given to a creditor to

have a debt or charge satisfied out of the real or personal property belonging

to a debtor. It always arises from a debt and can be created by agreement of

the parties (mortgage) or by operation of law (tax lien). A lien may be a general

lien, affecting all of the debtor's property, as in the case of a judgment

lien. It can also be a special lien, affecting only a specific property, as

when a mortgage is given on one piece of property.

Liens can be statutory or equitable,

voluntary or involuntary. For example, a mechanic's lien is an involuntary,

statutory, special lien, whereas a mortgage is a voluntary, equitable, special

lien.

At the initiation of a law suit, the

plaintiff who wishes to make known the claim against the property may do so by

filing a statutory notice of lis pendens or pendency of action. This should be

filed in the county in which the property is located, giving constructive

notice of a claim against the real property of the debtor.

Liens do not transfer title to the

property. Until foreclosure, the debtor retains title. Certain statutory liens

(mechanic's liens and judgments) become unenforceable after a lapse of time

from origination or recording unless a foreclosure suit is filed. The senior or

prior lien is normally determined by the date of recordation. State property

tax liens and assessments, however, take priority over all liens, even those

previously recorded.

Mortgages

The mortgage is the most typical

encumbrance against real property. It is a voluntary special lien, in that the

property owner voluntarily mortgages a specific property. A mortgage is a

means, recognized by law, by which property is pledged as security for the

payment of debt.

Most

states are "lien theory states" where the mortgagee (lender) acquires

a lien over the real property of the mortgagor (borrower) in order to secure a

debt. In other states, called "title theory states," the mortgagee

acquires some form of title to a mortgaged property in order to secure a debt.

The primary difference between lien theory and title theory states is the right

of mortgagees with respect to default. In the most strict sense in a lien

theory state, the mortgagor is entitled to possess until foreclosure, provided

the mortgage has no provisions to the contrary. In the most strict sense in a

title theory state, the mortgage conveys title to the mortgagee with

reconveyance to the mortgagor when the mortgage debt is satisfied.

Actually, the rights of the parties in

title theory states are treated substantially the same as those in lien theory

states. In the event of default by the mortgagor, the mortgagee may foreclose

on the mortgage and ultimately, if the mortgagor does not redeem (pay the debt plus

any accrued interest) during a stated period, the mortgagee may have the

mortgaged property sold at a public sale to satisfy the debt. If proceeds from

a foreclosure sale are insufficient to pay the amount of the debt, a deficiency

judgment will be entered against the defaulting mortgagor for the difference.

During the term of the mortgage, the mortgagor is the exclusive title holder of

the real property, but such real property is subject to the outstanding lien in

favor of the mortgagee.

Unpaid state, county, municipal, or

quasi-public (e.g., school board) real estate taxes may result in a special

lien against the taxed real property. The taxing entity may ultimately conduct

a tax sale of the affected real property to satisfy the debt.

Certain real property is exempted in

whole or in part from real estate taxation. The most typical examples of tax

exempt property are public libraries, free museums, public cemeteries,

non-profit schools, non-profit colleges and property used exclusively for

religious or charitable purposes.

Real property taxes (ad valorem taxes)

are apportioned according to the value of nonexempt property. The determination

of the property value is the duty of the county assessor, or duly elected

county officer. There are generally two methods of determining the assessed

valuation of real estate. The first method values property at fair market value

and deducts exemptions to determine the taxable valuation (assessment). This is

a market value assessment. The second method values property at fair market

value then applies a fractional percentage against the value to determine the

assessment in which exemptions are deducted to determine the net assessed

valuation. Such assessment is then used to determine the tax liability imposed

against each parcel of real property in the county. California is a fractional

assessment state.

Tax liens are usually enforced through

forced public sales of the affected real property. Generally, the owner of the

property is given a period of redemption during which time he may buy back the

real property for the sale price plus a penalty assessed as a percentage of the

price brought from the public sale. Tax (and special assessment) liens are

prior, superior, and paramount to all other liens, claims, or encumbrances of

whatever character, including those of a mortgagee, judgment creditor, or other

lienholder whose rights were performed prior to the date that the tax lien was

filed in the District Court judgment docket, located in the office of the county

clerk.

Special assessments are taxes or levies

customarily imposed against only those specific parcels of realty that will

benefit from a proposed public improvement. Whereas property taxes are levied

for the support of the general functions of government, special assessments

cover the cost of specific local improvements such as streets, sewers,

irrigation, and drainage.

The owner usually has the option of

paying special assessments in installments over several years with interest or

paying the balance in full at the beginning.

When property is sold, the sales contract

should specify which party is responsible for payment of the assessments, if

any, at the time of closing. Because of the increased property value generally

resulting from the improvement, the seller usually pays for all improvements

substantially completed by the closing date. Improvements not substantially

completed but authorized or in progress are usually assumed by the buyer.

Special assessments are generally

apportioned according to benefits received, rather than by the value of the

land and buildings being assessed. For example, in a residential subdivision,

the assessment for installation of storm drains, curbs and gutters is made on a

front-foot basis. The property owners are charged for each foot of that lot

that abuts the street being improved. In the case of a street being paved for

the first time, all nearby properties may share in the assessment in some

proportion based on proximity to the improvement.

Owners of condominiums may be subject to

special assessments if major improvements are made to the building such as

installation of automatic elevators or corridor carpeting.

A mechanic's lien is a statutory lien

(created by the legislature) in favor of those who furnish labor or materials

for the improvement of real property, not repairs. These liens tend to improve

the chances of such persons receiving compensation for the labor and materials

provided.

The lien obtained by a person furnishing

materials for such an improvement is called a materialman's lien, but the law

relating to both liens is the same, and both liens will be treated the same in

this discussion. Such statutory liens may be obtained by all persons, including

day laborers, who provide labor or materials for the improvement of real

property.

A mechanic's lien is superior to all

liens which were filed subsequent to the commencement of such labor or

provision of materials by the lien holder. This lien is also superior over any

lien of which the lien holder had no notice, and which was unrecorded at the

time of the commencement of the work or the providing of materials by the lien

holder. If the underlying debt is paid to the lien holder, the lien is

terminated or if the lien is proven invalid in a court of law, the lien is

terminated. If a valid lien exists, such lien may be discharged by the person

against whose interest such lien was filed by depositing with the county clerk

the amount of such claim in cash and executing a bond to the claim. In the case

of a lien in question, the same process may be used until the court can make a

determination.

Failure to pursue a mechanic's lien

within one year will terminate the lien. If enforcement is pursued and payment

on the debt is not forthcoming, the lien holder may have the affected real

property sold to satisfy the debt. If the affected property is a homestead,

certain conditions must have been met before the lien may attach to force sale

of the property (i.e., the improvements must have been agreed to by both

husband and wife).

(The following reprinted by permission

from the CalBRE Reference Book, p.96-101)

To convert the security for the lien into

money requires:

1.Timely recordation of a notice and

claim of lien (one document) in the county recorder's office in which the work

of improvement is located;

2. Perfection

of the recorded notice and claim of lien by the filing of an action (a lawsuit)

in the right court;

3.Recordation of a lis pendens;

4.Timely pursuit of the lawsuit to

judgment; and

5. Enforcement

of that judgment by a mechanic's lien foreclosure sale.

Persons specifically entitled to

mechanics' liens by virtue of the constitution and the statutes include the

following:

Mechanics Builders

Registered Lessors

of Equipment

Engineers Teamsters

Materialmen Artisans

Licensed

Land Draymen

Surveyors Architects

Contractors Union

Trust Fund

Machinists (Section

3111 Civil

Subcontractors Code)

Preliminary 20-Day Notice (Private Work)

The initial step in the perfection of a claim of

mechanic's lien for all claimants, except one under direct contract with the

owner, one performing actual labor for wages or an express trust fund as

defined in Civil Code Section 3111, is to give the preliminary 20-day notice

specified in Section 3097 of the Civil Code.

Each person serving a preliminary 20-day notice

may file (not record) that notice with the county recorder in which any portion

of the real property is located. The filed preliminary 20-day notice is not a

recordable document and, hence, is not entered into the county recorder's

indices which impart constructive notice. Filing of the preliminary 20-day

notice does not impart actual or constructive notice to any person of the

existence (or contents) of the filed preliminary 20-day notice. No duty of

inquiry on the part of any party to determine the existence or contents of the

preliminary 20-day notice is imposed by the filing. The purpose of filing the

preliminary 20-day notice is limited. It is intended to help those who filed

the preliminary 20-day notice get notice (from the county recorder by mail) of

recorded notices of completion and notices of cessation. Once the county

recorder records either a notice of completion or cessation, he/she is required

within 5 days after the recording of a notice of completion or notice of

cessation to mail to those persons who filed a preliminary 20-day notice,

notification that notice of completion or cessation has been recorded

Failure of the county recorder to mail the

notification to the person who filed the preliminary 20-day notice or failure

of those persons to receive notification shall not affect the period within

which a claim of lien is required to be recorded. The index maintained by the

recorder of filed preliminary 20-day notices must be separate from those

indices maintained by the county recorder of those official records of the

county which by law impart constructive notice.

Termination of the Lien

Voluntary release of the lien, normally after

payment of the underlying debt, will terminate the lien. If a mechanic's lien

claimant fails to commence an action to foreclose the claim of lien within 90

days after recording the claim of lien and if within that time no extended credit

is recorded, the lien is automatically null, void and of no further force and

effect.

If the lien is foreclosed by court action, there

may ultimately be a judicial sale of the property and payment to the lienholder

out of the proceeds.

Notice of No responsibility

The owner, or any person having or claiming any

interest in the land, may, within 10 days after obtaining knowledge of

construction, alteration, or repair give notice that he or she will not be

responsible for the work by posting a notice in some conspicuous place on the

property and recording a verified copy thereof. The notice must contain a

description of the property with the name and nature of title or interest of

the person giving it, name of the purchaser under the contract, if any, or lessee

if known and a statement that the person giving the notice will not be

responsible for any claims arising from the work of improvement. If such notice

is posted, the owner of the interest in the land may not have owner's interest

liened, provided the notice is recorded within the ten-day period.

The validity of a notice of nonresponsibility

cannot be determined from the official county records since they will not

disclose whether compliance has been made with the code requirements as to

posting on the premises. If such posting has not been made, a recorded notice

affords no protection from a mechanic's lien.

Release of lien bond

Owners and contractors disputing the correctness

or the validity of a recorded claim of mechanic's lien may record, either before

or after the commencement of an action to enforce the claim of lien, a release

lien bond in accordance with the provisions of Civil Code Section 3143.A proper

release of lien bond, properly recorded, is effective to "lift" or

release the claim of lien from the real property described in the release of

lien bond as well as any pending action brought to foreclose the claim of lien.

(End of CalBRE Reference Book excerpt).

Other liens affecting only one parcel of land

include vendee's lien, available to the buyer (vendee of real property in the

event of the seller's breach, vendor's lien, available to the seller (vendor)

where buyer does not pay the lien, available to the seller (vendor) where buyer

does not pay seller the purchase price, and attachment surety bond liens.

Unpaid specific taxes

Nonpayment of tax liabilities based upon such

taxes as state and federal income and/or estate taxes, corporate franchise

taxes, etc., generally causes a lien to be placed on all property owned by the

nonpaying party. If the specific tax is a state tax and the estate has not paid

such a tax, a lien is placed over all of the real and personal property

included in the estate. Clear title to a property cannot be given until tax

liens are discharged.

Decedent's debts

The debts of a decedent must be paid out of the

estate. It is not uncommon for the decedent to have included a provision in a

will which sets aside money or assets to pay outstanding debts. If no such

provision is present, or if a decedent dies intestate, the property of the

estate must be used to satisfy the debts. A lien against all estate property,

except for homestead property, exists on the basis of all just debts acquired

by the decedent while living. Personal property will be resorted to first to

satisfy such debts, but in the event that the personal property is insufficient

to pay the debts, resort may be had to real property contained in the estate of

the debtor.

A judgment is a judicial determination in a

legal action as to the rights and liabilities of the parties. The most common

legal judgment is one for money damages. Once a money judgment is obtained, the

judgment creditor (the person who has obtained the judgment) acquires a lien

over all property of the judgment debtor, except homestead property, if the

property is located in the same county as the court where such judgment was

rendered. By properly filing (docketing) such judgment lien in other counties

in which the judgment debtor owns property, the judgment creditor may obtain a lien

over most property owned by the debtor.

If the debtor fails to pay on the judgment, the

creditor may bring an action to have the debtor's property sold to satisfy the

judgment debt. The debtor's personal property will be sold first, but if the

sale of the personal property is insufficient to cover the judgment, the real

property over which the creditor has obtained a judgment lien will be sold to

satisfy the debt.

In California, as other states, ownership of

one's home is given certain protection by law. The concept or law of homestead

is founded on public policy considerations to prevent the loss of home and

disruption of family life. Many states have enacted homestead statutes to

protect the family from the claims of creditors. The homestead is the owner's

primary residence together with the land and surrounding buildings. Homestead

is established to do the following:

Protect one spouse from the other spouse selling

the home without their consent.

Protect the owner, whether married or single,

from forced sale to satisfy the claims of general creditors.

Insure an owner's widow, widower or minor

children will have a home safe from the claim's of certain creditors.

Note: The homestead designation will not prevent

claims for taxes and special assessments, mortgage liens, or mechanic's liens.

(The following is reprinted by permission from

the CalBRE Reference Book, p.110-113)

A homestead declaration does not restrict or

limit any right to convey or encumber the declared homestead.

To be effective, the declaration must be

recorded; when properly recorded, the declaration is prima facie evidence of

the facts contained therein; but off-record matters could prove otherwise.

Rights of Spouses. A married person who is not

the owner of an interest in the dwelling may execute, acknowledge, and record a

homestead declaration naming the other spouse who is an owner of an interest in

the dwelling as the declared homestead owner but at least one of the spouses

must reside in the dwelling as his or her principal dwelling at the time of

recording.

Either spouse can declare a homestead on the

community or quasi-community property, or on property held as tenants in common

or joint tenants, but cannot declare a homestead on the separate property of

the other spouse in which the declarant has no ownership interest. A homestead

cannot be declared after the homeowner files a petition in bankruptcy.

The homestead declaration does not protect the

homestead from all forced sales; e.g., it is subject to forced sale if a

judgment is obtained:

(1)prior to the recording of the homestead

declaration

(2)on debts secured by encumbrances on

the premises executed by the owner before the declaration was filed for record

and

(3) obligations

secured by mechanics', contractors', subcontractors', laborers', materialmen's

or vendors' liens on the premises. Voluntary encumbrances by the owner of the

homestead are not affected by a declaration of homestead. A mortgage or deed of

trust is an example of a voluntary encumbrance.

End of CalBRE Reference Book excerpt)